World War II Era

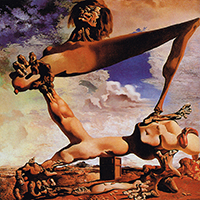

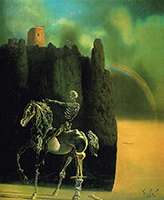

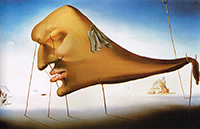

In the years immediately preceding and throughout World War II Dalí became even more prolific and produced many of his most iconic works.

Dalí's first visit to the United States in November 1934 attracted widespread press coverage. His second New York exhibition was held at the Julien Levy Gallery in November–December 1934 and was again a commercial and critical success. Dalí delivered three lectures on Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and other venues during which he told his audience for the first time that "the only difference between me and a madman is that I am not mad." The heiress Caresse Crosby, the inventor of the brassiere, organized a farewell fancy dress ball for Dalí on January 18th, 1935. Dalí wore a glass case on his chest containing a brassiere and Gala dressed as a woman giving birth through her head. A Paris newspaper later claimed that the Dalís had dressed as the Lindbergh baby and his kidnapper, a claim which Dalí denied.

While the majority of the Surrealist group had become increasingly associated with leftist politics, Dalí maintained an ambiguous position on the subject of the proper relationship between politics and art. Leading Surrealist André Breton accused Dalí of defending the "new" and "irrational" in "the Hitler phenomenon", but Dalí quickly rejected this claim, saying, "I am Hitlerian neither in fact nor intention". Dalí insisted that Surrealism could exist in an apolitical context and refused to explicitly denounce fascism. Later in 1934, Dalí was subjected to a "trial", in which he narrowly avoided being expelled from the Surrealist group. To this, Dalí retorted, "The difference between the Surrealists and me is that I am a Surrealist."

In 1936, Dalí took part in the London International Surrealist Exhibition. His lecture, titled "Fantômes paranoiaques authentiques," was delivered while wearing a deep-sea diving suit and helmet. He had arrived carrying a billiard cue and leading a pair of Russian wolfhounds, and had to have the helmet unscrewed as he gasped for breath. He commented that "I just wanted to show that I was 'plunging deeply' into the human mind."

The outbreak of World War II in September 1939 saw the Dalís in France. Following the German invasion they were able to escape because on June 20th, 1940 they were issued visas by Aristides de Sousa Mendes, Portuguese consul in Bordeaux, France. They crossed into Portugal and subsequently sailed on the Excambion from Lisbon to New York in August 1940. Dalí and Gala were to live in the United States for eight years, splitting their time between New York and the Monterey Peninsula, California.

Dalí spent the winter of 1940–41 at Hampton Manor, the residence of Caresse Crosby, in Caroline County, Virginia, where he worked on various projects including his autobiography and paintings for his upcoming exhibition.

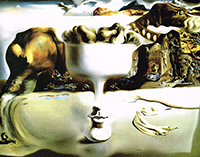

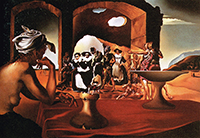

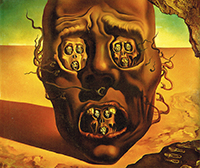

Dalí announced the death of the Surrealist movement and the return of classicism in his exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in April–May 1941. The exhibition included nineteen paintings (among them Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire and The Face of War) and other works. In his catalog essay and media comments Dalí proclaimed a return to form, control, structure and the Golden Section. Sales however were disappointing and the majority of critics did not believe there had been a major change in Dalí's work.

Dalí was the subject of a major joint retrospective exhibition with Joan Miró at MoMA from November 1941 to February 1942, Dalí being represented by forty-two paintings and sixteen drawings. Dalí's work attracted most of the attention of critics and the exhibition later toured eight American cities, enhancing his reputation in America.

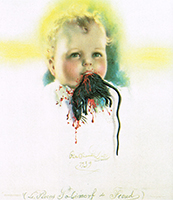

In October 1942, Dalí's autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí was published simultaneously in New York and London and was reviewed widely by the press. Time magazine's reviewer called it "one of the most irresistible books of the year". George Orwell later wrote a scathing review in the Saturday Book. A passage in the autobiography in which Dalí claimed that Buñuel was solely responsible for the anti-clericalism in the film L'Age d'Or may have indirectly led to Buñuel losing his position at MoMA in 1943. Dalí also published a novel, Hidden Faces in 1944 with less critical and commercial success.

In the catalog essay for his exhibition at the Knoedler Gallery in New York in 1943 Dalí continued his attack on the Surrealist movement, writing: "Surrealism will at least have served to give experimental proof that total sterility and attempts at automatizations have gone too far and have led to a totalitarian system. ...Today's laziness and the total lack of technique have reached their paroxysm in the psychological signification of the current use of the college [collage]". The critical response to the society portraits in the exhibition, however, was generally negative.

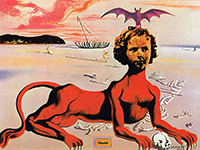

In November–December 1945 Dalí exhibited new work at the Bignou Gallery in New York. The exhibition included eleven oil paintings, watercolors, drawings and illustrations. Works included, Basket of Bread, Atomic and Uranian Melancholic Ideal, and My Wife Nude Contemplating her own Body Transformed into Steps, The Three Vertebrae of a Column, Sky and Architecture. The exhibition was notable for works in Dalí's new classicism style and those heralding his "atomic period".

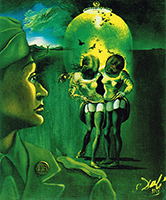

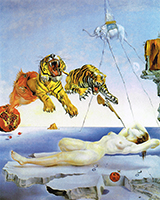

During the war years Dalí was also engaged in projects in various other fields. He executed designs for a number of ballets including Labyrinth (1942), Sentimental Colloquy, Mad Tristan, and The Cafe of Chinitas (all 1944). In 1945 he created the dream sequence for Alfred Hitchcock's film Spellbound. He also produced art work and designs for products such as perfumes, cosmetics, hosiery and ties.