Dalí's Formative Years

On February 6, 1921, Dalí's mother died of uterine cancer. Dalí was 16 years old and later said his mother's death "was the greatest blow I had experienced in my life. I worshipped her... I could not resign myself to the loss of a being on whom I counted to make invisible the unavoidable blemishes of my soul." After his wife's death, Dalí's father married her sister. Dalí did not resent this marriage, because he had great love and respect for his aunt.

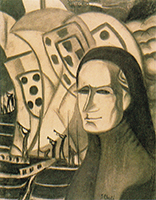

Early on, Dalí's paintings in which he experimented with Cubism earned him the most attention from his fellow students since there were no Cubist artists in Madrid at the time. Cabaret Scene, (1922) is a typical example of such work. Through his association with members of the Ultra group, Dalí became more acquainted with avant-garde movements, including Dada and Futurism. One of his earliest works to show a strong Futurist and Cubist influence was the watercolor Night-Walking Dreams, (1922). At this time, Dalí also read Freud and Lautréamont who were to have a profound influence on his work.

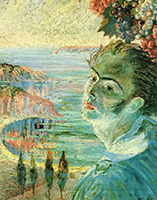

In April 1926 Dalí made his first trip to Paris where he met Pablo Picasso, whom he revered. Picasso had already heard favorable reports about Dalí from Joan Miró, a fellow Catalan who later introduced him to many Surrealist friends. As he developed his own style over the next few years, Dalí made a number of works strongly influenced by Picasso and Miró. Dalí was also influenced by the work of Yves Tanguy, and he later allegedly told Tanguy's niece, "I pinched everything from your uncle Yves."

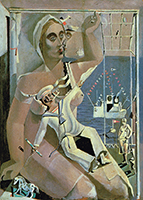

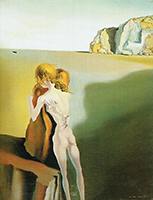

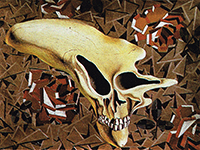

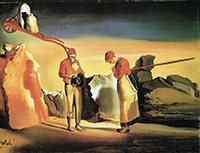

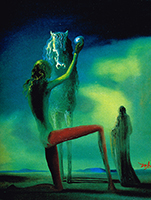

From 1927 Dalí's work became increasingly influenced by Surrealism. Two of these works, Honey is Sweeter than Blood, (1927), and Gadget and Hand, (1927) were shown at the annual Autumn Salon (Saló de tardor) in Barcelona in October 1927. Dalí described the earlier of these works, Honey is Sweeter than Blood, as "equidistant between Cubism and Surrealism". The works featured a number of elements that were to become characteristic of his Surrealist period including dreamlike images, precise draftsmanship, idiosyncratic inconography (such as rotting donkeys and dismembered bodies), and lighting and landscapes strongly evocative of his native Catalonia. The works provoked bemusement among the public and debate among critics about whether Dalí had become a Surrealist.

Influenced by his reading of Freud, Dalí increasingly introduced suggestive sexual imagery and symbolism into his work. He submitted Dialogue on the Beach (Unsatisfied Desires), (1928) to the Barcelona Autumn Salon for but the work was rejected because "it was not fit to be exhibited in any gallery habitually visited by the numerous public little prepared for certain surprises." The resulting scandal was widely covered in the Barcelona press and prompted a popular Madrid illustrated weekly to publish an interview with the now controversial artist.

Some trends in Dalí's work that would continue throughout his life were already evident in the 1920s. Dalí was influenced by many styles of art, ranging from the most academically classic, to the most cutting-edge avant-garde. His classical influences included Raphael, Bronzino, Francisco de Zurbarán, Vermeer and Velázquez. Exhibitions of his works attracted much attention and a mixture of praise and puzzled debate from critics who noted an apparent inconsistency in his work by the use of both traditional and modern techniques and motifs between works and within individual works.

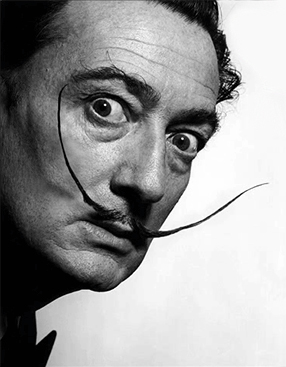

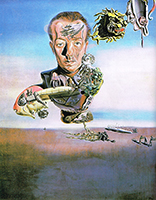

In the mid-1920s Dalí grew a neatly trimmed moustache. In later decades he cultivated a more flamboyant one in the manner of 17th-century Spanish master painter Diego Velázquez, and this moustache became a well known Dalí icon.

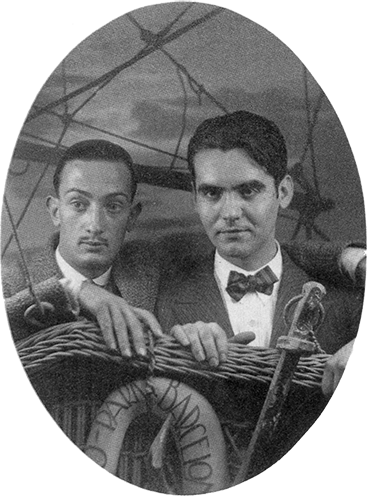

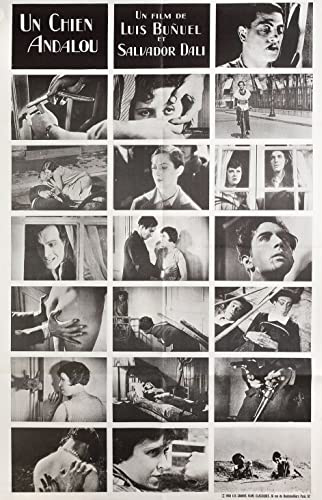

In 1929, Dalí collaborated with Surrealist film director Luis Buñuel on the short film, Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog). His main contribution was to help Buñuel write the script for the film. Dalí later claimed to have also played a significant role in the filming of the project, but this is not substantiated by contemporary accounts. In August 1929, Dalí met his lifelong muse and future wife Gala, born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova. She was a Russian immigrant ten years his senior, who at that time was married to Surrealist poet Paul Éluard.

In works such as The First Days of Spring, The Great Masturbator and The Lugubrious Game Dalí continued his exploration of the themes of sexual anxiety and unconscious desires. Dalí's first Paris exhibition was at the recently opened Goemans Gallery in November 1929 and featured eleven works. In his preface to the catalog, André Breton described Dalí's new work as "the most hallucinatory that has been produced up to now." The exhibition was a commercial success but the critical response was divided. In the same year, Dalí officially joined the Surrealist group in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris. The Surrealists hailed what Dalí was later to call his paranoiac-critical method of accessing the subconscious for greater artistic creativity.

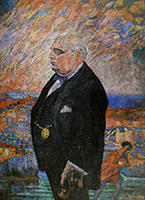

Meanwhile, Dalí's relationship with his father was close to rupture. Don Salvador Dalí y Cusi strongly disapproved of his son's romance with Gala, and saw his connection to the Surrealists as a bad influence on his morals. The final straw was when Don Salvador read in a Barcelona newspaper that his son had recently exhibited in Paris a drawing of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Christ, with a provocative inscription: "Sometimes, I spit for fun on my mother's portrait". Outraged, Don Salvador demanded that his son recant publicly. Dalí refused, perhaps out of fear of expulsion from the Surrealist group, and was violently thrown out of his paternal home on December 28th, 1929. His father told him that he would be disinherited, and that he should never set foot in Cadaqués again. The following summer, Dalí and Gala rented a small fisherman's cabin in a nearby bay at Port Lligat. He soon bought the cabin, and over the years enlarged it by buying neighboring ones, gradually building his beloved villa by the sea. Dalí's father would eventually relent and come to accept his son's companion.

In 1930, Dalí painted one of his most famous works, The Persistence of Memory, which developed a surrealistic image of soft, melting pocket watches. The general interpretation of the work is that the soft watches are a rejection of the assumption that time is rigid or deterministic. This idea is supported by other images in the work, such as the wide expanding landscape, and other limp watches shown being devoured by ants.

Dalí had two important exhibitions at the Pierre Colle Gallery in Paris in June 1931 and May–June 1932. The earlier exhibition included sixteen paintings, of which The Persistence of Memory attracted the most attention. Some of the notable features of the exhibitions were the proliferation of images and references to Dalí's muse Gala and the inclusion of Surrealist Objects such as, Hypnagogic Clock, and, Clock Based on the Decomposition of Bodies. Dalí's last, and largest, exhibition at the Pierre Colle Gallery was held in June 1933 and included twenty-two paintings, ten drawings and two objects. One critic noted Dalí's precise draftsmanship and attention to detail, describing him as a "paranoiac of geometrical temperament". Dalí's first New York exhibition was held at Julien Levy's gallery in November–December 1933. The exhibition featured twenty-six works and was a commercial and critical success. The New Yorker critic praised the precision and lack of sentimentality in the works, calling them "frozen nightmares".

Dalí and Gala, having lived together since 1929, were civilly married on January 30th, 1934 in Paris. They later remarried in a Church ceremony on August 8th, 1958 at Sant Martí Vell. In addition to inspiring many artworks throughout her life, Gala would act as Dalí's business manager, supporting their extravagant lifestyle while adeptly steering clear of insolvency. Gala, who herself engaged in extra-marital affairs, seemed to tolerate Dalí's dalliances with younger muses, secure in her own position as his primary relationship. Dalí continued to paint her as they both aged, producing sympathetic and adoring images of her. The "tense, complex and ambiguous relationship" lasting over 50 years would later become the subject of an opera, Jo, Dalí (I, Dalí) by Catalan composer Xavier Benguerel.